It happened in Detroit on a Super Bowl Sunday in 1972. FBI headquarters had ordered a cross country gambling raid, looking to rope in 1,000 bookies and shut down as many parlors as possible in a one-day raid. One-third of those arrests were expected to come out of the Detroit office. The gambling houses would need to be hit hot and fast, since they were always on the look-out for such attacks, especially on high-level gambling days like Super Bowl Sunday. “I made three arrests that day,” John Douglas recalls. “One of them turned the direction of my life completely around. His name was Frank and he was in his early 30’s, sitting in the backseat of the unmarked, me next to him. He looked like a young Steve McQueen, thin, strong, and cool and we had just taken down his gambling house. He was staring out the car window, a heavy rain pouring down.

“We had a few minutes before we headed off to booking. I looked at him and asked, ‘Why do you do this shit? Every year or so, you get arrested, the rest of the time always wondering when we’re going to come through that front door. Sometimes end up doing a few years in jail. What’s the point of it all?’ He glanced over at me and smiled. ‘You don’t get it, do you kid?’ he said. He turned back toward the window, rain drops streaking down the sides of the glass. Pick out one of those rain drops and I’ll pick another and I’ll bet you any amount that mine makes it to the bottom before yours. You see my point? We don’t need a Super Bowl. All we need are two rain drops. We are who we are and not you or anybody like you is ever going to change us. Not ever.’

“And that was it,” Douglas says. “’We are who we are.’ If it was true of the gambler, then would that mind set be true of any other type of criminal? Would that thinking fit all types of criminal? That’s what I wanted to find out.”

On that rainy day in Detroit, in the mind of John Douglas, a young field agent for the FBI, the idea of criminal profiling took hold and never let go. He went to graduate school, spent as many of his free hours as he could manage watching homicide detectives and medical examiners go through the paces of their jobs. He studied criminal patterns, looking for any similarities in motives and actions. “The FBI had a behavioral Science Unit but it was strictly instructional,” Douglas says. “I was going to change that. I was looking to make it operational. I knew my plan would drive the Bureau crazy, but I also knew if it was implemented properly, it would work. When I was finally assigned to Quantico, I was by far the youngest of the 110 instructors they had. I was 32, had the degrees and the experience. I would sit in on the classes of the other instructors and realize they had never worked a case. They got all their information off books or from what people told them. To me, that was an ineffective use of both time and the available science.”

Douglas attacked his field of study. He accelerated his learning curve by traveling the country, working out of the LA bureau for two weeks, then moving on to Portland for a short stay and then over to Chicago. “We were presenting the Charles Manson case around that time,” he says. “But no FBI agent had ever talked to him. I went to talk to him. I went to talk to all of them.”

John Douglas has spent time in the company of every serial killer ever captured and put behind bars. He goes with full knowledge of their crimes. He comes out with the reasons why and the patterns with which they were committed. “When I first started doing the interviews,” he says, “I went in wearing a suit. I realized quickly that was a mistake. They size you up, same way I’m sizing them up. You dress down; you go in not like a cop, but like someone eager to hear their story. They love to talk, every single one of them, and I’m a good listener.”

He walks into that room, confronting the most evil that walk among us, bolstered by all his professional experience—his years as a hostage negotiator, member of an FBI SWAT team, creator of the FBI’s Criminal Profiling Program, unit chief of the Investigative Support Unit, criminal psychology instructor—and puts those skills to the test. He has never failed to leave without a piece of information that will help capture the next serial killer law officers are hunting down. “I let them control the room,” Douglas says of his interviews. “I never put their back to a door or a window. In fact, I let them face the door or the window. I allow them to fantasize about their escape. You listen to their words and then restate the content back to them, allow them to hear their own words repeated, reinforcing their message. They can read people, their posture, the way that they walk, move. They see a woman in a bar and know if she’s there just for a drink or if she’s depressed and in need. Serial killers are highly skilled in how they approach their victims, as are rapists. Sometimes, as in the case of Manson, they run the risk of losing control of the group. The followers like who they hate and the reasons for it, but there’s not enough movement for them. They got the song, but where’s the dance? They embrace the philosophy, but not the speed with which it is applied.”

The conversations with these killers can often be nauseating and always troubling to listen to. The only revenge for a master profiler like John Douglas is to use the information he gains from these men to enter their dark spaces, where he will find the motives for their gruesome acts. “They love to talk about the crimes; they have no remorse in that area. You work it to where he feels as if he’s talking to someone like himself. You laugh along with them, all the while your insides are churning over the horrors this guy has committed. Douglas recounts one such conversation, with Charles Davis, the son of a cop, who had killed seven people. ‘Something happened to you,’ I said to him. ‘Something that set you off. Some conflict.’ Davis said it was a fight with his father. Now, he was a low achiever and in his late 20s at the time, which is the age at which they usually surface. He was a preferential killer. Would wait in a parking lot outside a bar until he saw a girl he liked and then get the plate number of her car. With that he would call a friend he know on the force and get a name. Goes inside the bar, tells the bartender a girl left the lights on in her car and then waits for her to come out. He grabs her, rapes and kills her in her own car. He told me about all the rapes and the murders and then I brought him back to the first one. ‘Something went wrong there,’ I said to him. ‘You didn’t want to kill her, but she said something to you that took it too far. You had no choice then. You had to kill her.’ He nodded and then very slowly said, ‘She told me her husband was sick, he was dying. It got to me.’

“I stared at him,” Douglas remembers, then suggested, ‘But she saw you and you knew you had to kill her. So you took something from her.’ He sat up straight and turned beet red. I got him to go back in time and rewind the CD in his brain. ‘I went through her wallet and found a photo of her, her husband and a dog.’ Now, at this point, you ask no more questions. You make statements. ‘You went back to her grave site,’ I said. ‘With that photo. You went back to the cemetery and did something with that photo.’ Davis nodded. ‘I buried the photo next to her,’ he said. I stared at him for a while and then turned and walked out of the room.”

John Douglas would work as many as 100 cases at a time. His office would be a mountain of photos, police and autopsy reports, photos of the crime scene and of the community involved. Often working with no suspect information at all, he would manage to break down a case. “It takes time,” Douglas says. “You need to walk in the shoes of both the victim and the killer. It is a long and difficult process. Two years of training, then about five years before you get to know what you’re doing. You must imagine what the victim of the crime experienced. Then you must imagine the criminal committing the crime and find the pattern. The more bizarre the case, the easier it is to break down. The focus is always on the behavior. What made him go out and do what he did. If and when you can do that, you can then focus on your suspect and hunt him down.”

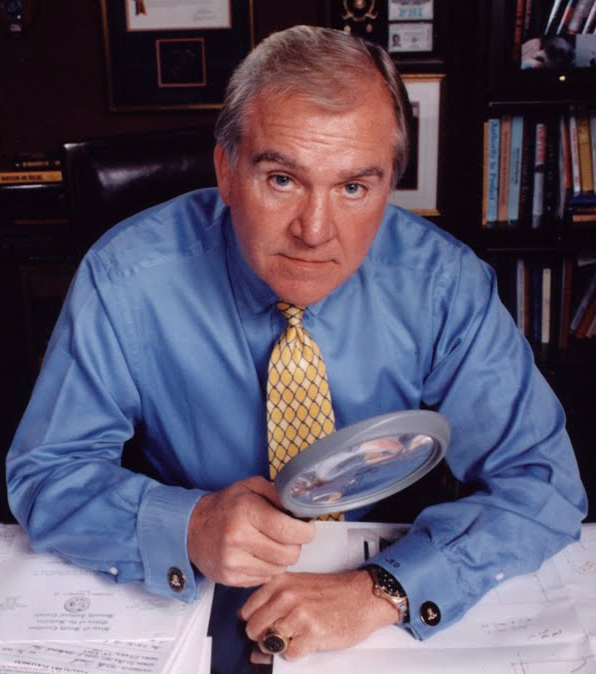

John Douglas is the world’s most famous profiler and the best we have in a field now over-run with so many who claim to hold the title without having accomplished much of anything. He has been portrayed in a number of feature films—he is the model for the Jack Crawford character and was played by Scott Glenn in “The Silence of the Lambs”; Dennis Farina in “Manhunter”; Harvey Keitel in “Red Dragon.” He was also used as the model for the profilers in two TV series: “Millennium” and “Profiler.” At the moment, HBO is developing a series based on Douglas’ first book, “Mind Hunter,” to be directed by David Fincher. He has written a number of bestselling works of non-fiction and two novels. He retired from the FBI in 1995 and now travels the world, brought in by police departments in need of answers, helping track down the killers who live among us.

Douglas was born in Brooklyn and moved to a small town on Long Island when he was eight. He comes from a working class background (his father worked for the Brooklyn Eagle and Newsday, typographical department) and initially sought a career path very different than the one with which he found fame—veterinarian. “I got into a Farm Cadet program to get some experience,” he says. “My grades were so-so but I figured working the program which I did for three summers would help. Well, I didn’t get into Cornell, which was my school of choice, and went to Montana State College instead. I bombed out of that school, came back to New York and soon after that joined the Air Force. Many years later, I was asked to speak at Cornell. I went up there, about 1,000 people in the crowd, and told them I was rejected by them because I wasn’t good enough. You just don’t know. You never know how things in your life turn out.”

It was during his Air Force years that Douglas was first approached by the FBI, through a mutual friend of the base commander. Douglas didn’t exactly jump at the opportunity. He had some concerns—he had been caught twice in Montana with possession of alcohol and thought that would rule him out. He was in excellent physical shape but at 6’2, he weighed in at 215 pounds. “My weight was a problem, even though I was in top condition. No agent of the Bureau could weigh more than 195 pounds. The only one who could go over that was J. Edgar Hoover. He followed a military weight pattern. It was a shame in many ways. They had potential agents with exceptional backgrounds who just couldn’t get down to that weight. I worked at losing the weight and on December 14, 1970 the orders arrived which directed me to go to Washington, D.C. My dad bought me three suits and two pair of wing tips. I was 25 when I was accepted, the youngest in a class of 50.”

The starting salary back then was $9,000 which would get kicked up to $13,300 after completing the training program. It wasn’t easy money. “The Bureau excelled at making us paranoid,” Douglas recalls of his rookie days. “You have to go out and get your own place, they give you a badge, swear you in and then tell you that you can’t meet any Russians. That makes you afraid to meet any girls out of fear you were being set up. Hoover was still alive and the fear senior agents had toward the Director was palpable. On your last training day, you are given a gun with six bullets and assigned out of town as fast as possible.”

There were other Bureau obstacles that needed to be overcome. “Hoover wanted us to wear suits and hats and drive dark colored sedans with no air conditioner and the windows down. It was a crazy time. I was assigned to a reactive squad, chasing down selective service violations and fugitives. Many times the draft dodgers had already been caught and sent to the front lines and been killed in duty and here we come in only to be told by a grieving father that their son was dead. You lose any sense of idealism fast dealing with stuff like that.”

Douglas got past those fuzzy early days and built the FBI’s serial Crime Unit into the best of its kind in the world and even that came with its own share of obstacles. “We don’t go in and kick down doors,” Douglas says. “We are coaches who are invited in by local police. We don’t make the arrests, they do. And very often, the rank and file, the detectives working the case, don’t really want us there. That’s their turf and we’re stepping on it. But none of that was ever my concern. I was after one thing and one thing only—the killer.”

Sometimes, at great risk to his own health. While working the Green River Case in Seattle, Douglas came down with viral encephalitis. It was December of 1983 and Douglas was only 38 years old. But the work had taken its toll—he had nailed Wayne Williams, the Atlanta Child Murderer, tagging him as the first African-American serial killer; he was working the Robert Hansen case in Alaska, a madmen picking up prostitutes and flying them out into the middle of nowhere in order to hunt them like animals; he was on the Yorkshire Ripper case in England and the Trailside Killer case in San Francisco—and his body simply surrendered to the stress, the hours, the pressure of dealing with the deadliest of our species.

John Douglas is, in many ways, as close to an American hero as we have going for us right now. He performs a task few are capable of and his efforts have saved unknown numbers of lives. He is soft-spoken, funny and great company. He is a family man who helped raise two daughters and a son. He makes the science of profiling seem much easier than it painstakingly is, combing it with a unique ability to read the motives and methods of the deadly prey he haunts. “With the Green River killer, it struck me that the police had their suspect,” Douglas says. “They had interviewed him a number of times and even gave him two polygraphs, both of which he passed. But I knew why he passed them. He didn’t his crimes—murdering nearly 60 women, all of whom were prostitutes—as evil. In his mind, he was doing a public service by ridding the streets of these women. That was the reason for his crimes. It was as sinister and as simple as all that.”

Across the years and through the hundreds of cases, there have been death threats made to both Douglas and to members of his family. Douglas doesn’t dismiss these but realizes they are part of the job. “There was only one time I lost control,” he says. “I was working from home in the evening; my girls where in their teens then. Case I was on was pretty disturbing—a man raping young girls and then burying them alive. A few threats had been put to me and I was aware of them and the Unit was on top of it. Anyway, I took a break and went in to check on my kids. The door to my daughter’s bedroom was open and her bed was empty. She was my youngest, about the same age the suspect was targeting. I rushed back downstairs and noticed the front door was slightly ajar. That’s when the panic hit me. The guy had come into my home. I grabbed my gun, jumped into the car and drove through the streets of my neighborhood pretty angry at myself and frightened for my daughter. I spotted her a few blocks from home. She had gone out for a walk with a young boy she liked.

“But that feeling stays with you,” Douglas admits. “I know what’s on the other end. I’ve seen too many other parents lose a child, lose someone they love to a horror they could never imagine. I’ve done everything I can to bring an end to those feelings, to bring these killers in before they take one more life, cost one more father, mother, husband or wife someone they love. It’s what I do.”

He has never been wrong. He cleared Jon Benet Ramsey’s parents long before the DNA ever proved their innocence. He is stressing the innocence of “The West Memphis Three,” attempting to clear three teens of the murders of three eight-year-old boys. Prosecutors have argued the children died as part of a satanic ritual. Douglas claims the murders were “personal cause homicides.” The teens have been convicted and the case is currently being appealed in both state and federal court. Douglas is also claiming the innocence of Amanda Knox, the young American girl convicted of murder in an Italian court. “She is so clearly not the killer,” Douglas says. “It’s an injustice she’s even behind bars.”

Douglas is the lawman they fear the most, the one who knows their secrets, who has plumbed the depths of their madness. He studies these monsters, learns the patterns of their bizarre behavior and rituals (one serial killer would bury his victims and then weeks later take his wife and children to the very site for a picnic), knows them so well he begins to think along their lines, anticipating their next move. He knows the buttons that need to be pushed before they are even pressed. And it is then that he makes his move, going in armed with the information needed for the police to go out and put a grab on their suspect and end yet another plague of vicious murders.

The FBI Behavioral Science Unit is now the most useful tool we have against the serial killers who live among us. The Criminal Profiling Program is studied and copied by a number of police departments around the world. John Douglas was the man responsible for both achievements. “I’ve interviewed them all—from The Son of Sam to Ted Bundy, Manson, John Wayne Gacy, Richard Speck, Donald Harvey—and learned as much as I could from them while I was in their company. We can never eliminate them. There’s just too many out there with a need to kill, a thirst for murder. But we have the tools now to bring the chase to them a lot sooner and bring them to an end a lot faster.”

All of it because of his own pioneering work.

John Douglas’ hair is greyer now, and though his body is still work-out hard, he might not be as fast out of the gate as he was when he first picked up that Bureau shield. But the passing years have only increased his capacity for reading the criminal mind and reacting with the speed necessary to catch what at times must seem like an invisible prey.

John Douglas was our first Profiler and he remains our best.

He is the constant in a serial killer’s disturbed dreams, their worst nightmare come to life.

He is the only one who can make them taste the fear they so cruelly inflict on others.

The only one.

If he is the one who knows the secrets of serial killers, it’s partly because, like BTK, Robert Hansen, Robert Yates, Russell Williams, etc., he’s an aviator. He was in the air force and there is a connection between serial killers and aviation. There are as many aviators as truckers which you would not suspect. If it was just a navigation thing, then there would be a whole lot more truckers like the I-5 killer by proportion. That’s not the case. So what is the connection? I don’t think Douglas would even admit to such a link. He might have a blindside for air force and aviators. http://xtremepsychology.proboards.com/thread/36/serial-killing-aviation

LikeLike

FBI can’t make any sense out of the Las Vegas shooter.

He’s a pilot.

http://xtremepsychology.proboards.com/thread/140/shooter-stephen-paddock-license-planes

LikeLike

I have noticed you don’t monetize your website, don’t waste

your traffic, you can earn extra bucks every month because you’ve got high quality content.

If you want to know how to make extra money, search for:

best adsense alternative Wrastain’s tools

LikeLike